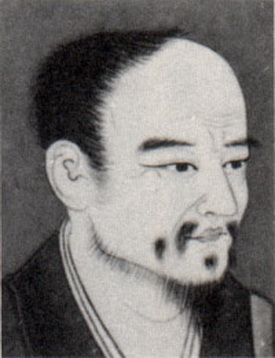

Torei Enji, a disciple and dharma heir of the great Japanese Rinzai Zen teacher Hakuin, once wrote a letter to a samurai to encourage his practice. This letter is now known as "A Whip for a Good Horse." Before I dive in, a note on the title. In the Dhammapada, the Buddha states, "Be like a good horse; touched gently by the whip, the horse moves forward with power and energy. Have an abundance of confidence, good conduct, effort, concentration. Be aware and attentive. Put aside this great mass of suffering." So the title of this reading is inspired by the Buddha's teaching, which invites us to be responsive in our practice in order to alleviate suffering for ourselves and all beings.

Part 1

In Part 1 of this abridged letter, as demarcated in Living Vow Zen's sutra book, Tori Enji writes: “Contemplating these four transcendences – impermanence, suffering, emptiness, selflessness – and seeking the way of enlightenment is called the four seals of the Dharma. This is the essential gateway. When you understand the mind darkened by ignorance and see its real nature, then ignorance becomes identical to the enlightened nature. Then the 12 links of dependent origination all accord with the right way and eventually arrive at the great realization of liberation."

Last night I watched this animated series called Midnight Gospel. It is bizarre. And I highly recommend it. The animation is two dimensional, colorful, murderous scenes of creatures disemboweling each other. What it actually is is a podcast, and the interviewer, Clancy Gilroy played by Duncan Trussell, questions guests. There are eight interviews and they took these interviews, which are genuine, and animated them, creating these simulated realities that these characters travel through as they talk.

Many of the interviews are actually about meditation, and he interviews a number of meditation teachers and folks of some renown, but my favorite episode is the last where he actually interviews his mother. She is dying; she had stage 4 cancer in real life, and he asked her if he could interview her for his podcast. She agreed, and their conversation is just beautiful.

But facing his mother's death for this interview is a very powerful lesson, and she's able to remain very present with him in this interview and to meet him in his emotional breaking down, his witnessing of her imminent death, and they talk very openly about it. And this ability for them to be there together in this grief is just such a powerful healing moment for both of them, especially for him -- to be with her and love her so openly and devotedly.

But what’s interesting is that the pathway to his healing love is directly through his grief. They talk about how in every person’s life a tornado comes, metaphorically speaking, and you’re left changed by that forever. These are the moments of reckoning and transformation that are available to us all.

Undoubtedly we’ve all faced these moments in our lives, losing people whom we adore – these transcendencies including impermanence and suffering as part of the essential gateway. I think we might prefer if the essential gateway were fun happy roller coaster rides and movies and cotton candy, and of course those are also dharma gates, but Buddhism includes acknowledging what we think of as suffering in our lives and practicing with that in a very conscious way, which is quite different from maybe our ways of dealing with pain or suffering that we have practiced over the course of our lives. We may find at some point that we've tried everything else, many different strategies, and nothing else really worked to alleviate suffering, so we come to practice Zen both hopeful and perhaps a little bit defeated having worked so hard at keeping an awesome body, and it falls apart, or at protecting the people we love, and still harm comes to them. And that sense of activity wears us out. Chogyam Trungpa says, “It's hopeless, it's truly hopeless,” and the same podcast narrator talks about how Trungpa really meant it.

It does seem that the dharma gate for many of us is this courageous willingness to turn toward that which we may have spent many years avoiding -- life as it actually is, which includes pain and loss -- and perhaps we've realized that setting the graveyard behind rows and rows of evergreen trees doesn't mean that people don't die. Hiding them from view does not mean we don’t lose people we love. Watching beautiful young people on TV doesn’t mean we don’t get older. We can’t escape into these fantasies, and this is the beginning of the path, almost a path of giving up, a path of realizing, "it's hopeless. It's just hopeless. I just can't do it anymore. I just can't fix everything. I can’t even fix myself." It’s like swallowing a hot, iron ball in your gut and there's nothing to be done with it, and it may form as a kind of burning anxiety or a grief that sneaks up on us in quiet moments. We feel it in so many different ways, this this kind of underlying existential dread that we often just avoid by scrolling on our phones, massive amounts of a beer or whatever... It may be we each have our different ways of escape, but we find that it's there waiting for us. We shut off the phone, lie down in the dark, and there’s our demon.

What a powerful thing this practice is, the courage to decide, "I’m going to stop running away. I'm going to just face it. I'm just going to face the thing that frightens me. I'm just going to be with it. I'm not going to escape into chatter. I'm not going to escape into false promises. I'm just going to sit here and be with whatever this trouble is." We turn the light around and shine it within.

And in this podcast, he sits down with his mother and he says that her dying, it's so hard, and she says, "yes it is," and he says, "so what do you do?" and she says, "you cry!” How’s that for a beautiful dharma teaching? How about you just be what you are. If you're scared, just be scared. This benefits all beings. Being with our own pain compassionately allows us to do the same with others without needing to push them away.

But we have a kind of protective set of mechanisms at work most of the time. Trungpa calls it the armor we put on. I think of it as the hamster wheel of escape -- the many things that we do to try to avoid feeling what we just feel. And as I say, they don't really work, these escapes. The pain, the trauma, it all just gets stored up in the cells of our bodies, one wound after another, and when we sit on the cushion at first, even for a while, we begin to metabolize these wounds. The cells of our bodies, they begin to unfold and release what we have been holding for years, in fact what we have probably inherited after countless generations, woven into the cells of our bodies. This is our store consciousness, our habit minds, much of it unconscious, at least initially. We might like to keep it that way, but in sitting, it all begins to emerge and unfold. And we think, why did I start this practice? I feel worse! That’s often true, we often can feel worse maybe even for a while.

But with practice, with just ongoing courage – even perhaps after taking breaks when we lose our faith – but once we’ve begun to taste this practice in a deep way, we may realize that nothing else is as deeply healing. Because when we allow ourselves to be exactly what we are, our tears fall, and every tear is healing not only ourselves but the world. Generations worth of wounds healed.

And what they talk about in the end of this podcast is the way that this grief is of course just another face of love. In the Buddhist tradition we tend to use the word compassion. Just compassion. A great kind of beauty in it. We have to experience that for ourselves. We have to see that for ourselves. Our great fear of death even. We may have a fear because why? Because we love life! it's so simple. We don’t want to lose everything and everybody we love.

Why would we try to pretend, "I'm cool with losing you." It hurts. That's part of love; that’s part of the beauty of love. Avoid the that particular face of love -- grief, and maybe the fear that we have about losing people, losing things, losing situations, losing places and life that we love -- if we avoid feeling these things, then we avoid the love too, because they are one. We can end up living a kind of plastic brittle existence, our heart not really touched by the intimacy of life.

And I think we come to practice because we want that back. We want to feel alive again.

So no, it isn't always easy. It hurts to have the heart break and open, but it's worth it because in that breaking open, we find our deep appreciation of life and the people in our lives.

You may find yourself randomly dancing in the kitchen sunlight. Touched by the beauty of life. Maybe with tears in your eyes.

So this dharma gate of suffering, often felt because of impermanence, reveals to us love and selflessness, because we find that everything we encounter, even these deepest fears, are shapeshifting and have no fixed essence but transform before our eyes, often into compassion and joy when we allow them to unfold.

We just have to BE it, not separate, and it unfolds, and we find there's actually nothing there to hold onto, and this is a dharma gate to impermanence and boundlessness that doesn't separate and protect and isolate itself out of fear of pain.

This is the essential gateway. "When you understand the mind darkened by ignorance and see its real nature, then ignorance becomes identical to the enlightened nature."

Of course we can do things to alleviate suffering where possible. But that’s not really what our sitting on the cushion is about. Our zazen is about meeting ourselves exactly as we are, giving ourselves permission to be exactly as we are. This mind of ignorance, of shame, of grief -- we imagine, “this can’t be enlightenment!” It can’t be my anger or my fear. We just believe that narrative so deeply, believe that we're supposed to be something other than what we are. It can't be my trauma or our collective trauma. And so we continue down that that path of trying to escape what we are, which is utterly futile, repressing things – but it is just what we are in the moment. So we are actually lying to ourselves. That is what is so futile about it.

What a courageous thing to sit here together, to decide to allow our hearts to just be as they are, to stop running away. To let ourselves love and be heartbroken and to feel it all, to let our hearts be touched by the world, to let ourselves be intimate with the world, with this moment. And to do this with the support of each other, to know that everybody here is in it with us. We’re not alone in this journey, in this practice of meeting ourselves and each other in this profoundly intimate way, this so vulnerable path.

Then we see that our grief is our love, that this thing that we have been thinking cannot be "it" is precisely "it,' is precisely emptiness, is precisely selfless, boundless intimacy. “Then the 12 links of dependent origination all accord with the right way, and we eventually arrive at the great realization of liberation."

Not liberation from what we are, but liberation into what we are.

Part 2

Part two of Enji's letter deepens his themes by discussing three important Buddhist teachings -- the twelve links of dependent origination, the six realms, and the six paramitas. (I have given separate talks about each of these teachings, and you can find them on Morning Star Zen Sangha's website. I invite you to check them out.) Below, I consider a bit more philosophically what Enji implies about how these 3 important teachings relate with each other, then dive into parts 3 and 4 of his letter.

- ignorance, the root belief that things exist as separate entities with fixed essences.

- Volition is the desire to protect our personal existence.

- Name and form distinguish my body from everything else and divide reality into this and that.

- Consciousness tries to pin things down into fixed categories.

- Sense faculties are often interpreted as inside the mind.

- Contact is the way we view objects as external to us — the other side of this dualistic notion of senses and objects.

- Feelings can be a burden to us when misconceived as nouns and when categorized as good and bad.

- Craving is the way we seek "good" feelings (without recognizing that the seeking itself is painful).

- Clinging results when we try to hold onto things that produce "good" feelings.

- Becoming describes the way our craving, clinging, and their corollary, aversion, become habit minds that drive our lives. These are the three poisons, the basic engine that drive us to be reborn endlessly in the six realms, metaphorically speaking. More on this below.

- Birth is the notion of a separate self and an external world.

- Old age and death arise once we believe we exist as separate entities.

It is true in a relative sense that I am not you, and you are not me. Recognizing relative truths allows us to distinguish "between a hawk and a handsaw." However, because we tend to be Aristotelian in our logic and adhere to the principle of noncontradiction, we often neglect the awareness that we are also utterly interwoven. Both sides of this coin are true -- we are separate waves, and we are one body of water.